The Prove

It Project

By Jessica Suriano

The Prove

It Project

By Jessica Suriano

The Problems: Students reported sexual assaults by faculty, in dorms and at fraternities. Then they heard the responses.

A University of Arizona assistant professor and a graduate student met for drinks in a downtown Tucson bar. She had a glass of red wine. After starting a second drink, she “experienced a complete blackout for several hours,” she later reported.

She woke up naked in a bed at an apartment belonging to a friend of the professor.

They had sex while she was impaired, the professor later told her, according to the complaint the student filed with the university. And they had sex again the next morning when she still felt “disoriented and incapable of consent.”

The student reported the 2017 incident in a complaint to UA’s Office of Institutional Equity, which is supposed to support “efforts to uphold the university’s commitment to creating and maintaining a working and learning environment that is inclusive and free of discriminatory conduct,” and act as “objective fact-finders,” according to its website.

The UA investigated internally, and the case crawled forward for nearly seven months. Nathan Waite Stupiansky, a public health professor who was director of adolescent studies, completed his last day at the school at the end of June 2018.

Tucson Police Department has an ongoing criminal investigation into the allegations, but Stupiansky’s lawyer denies any wrongdoing.

To the woman who made the complaint, the entire process reporting through the university was confusing, lacked transparency and never seemed to address her needs as a victim.

And her experience is not unique.

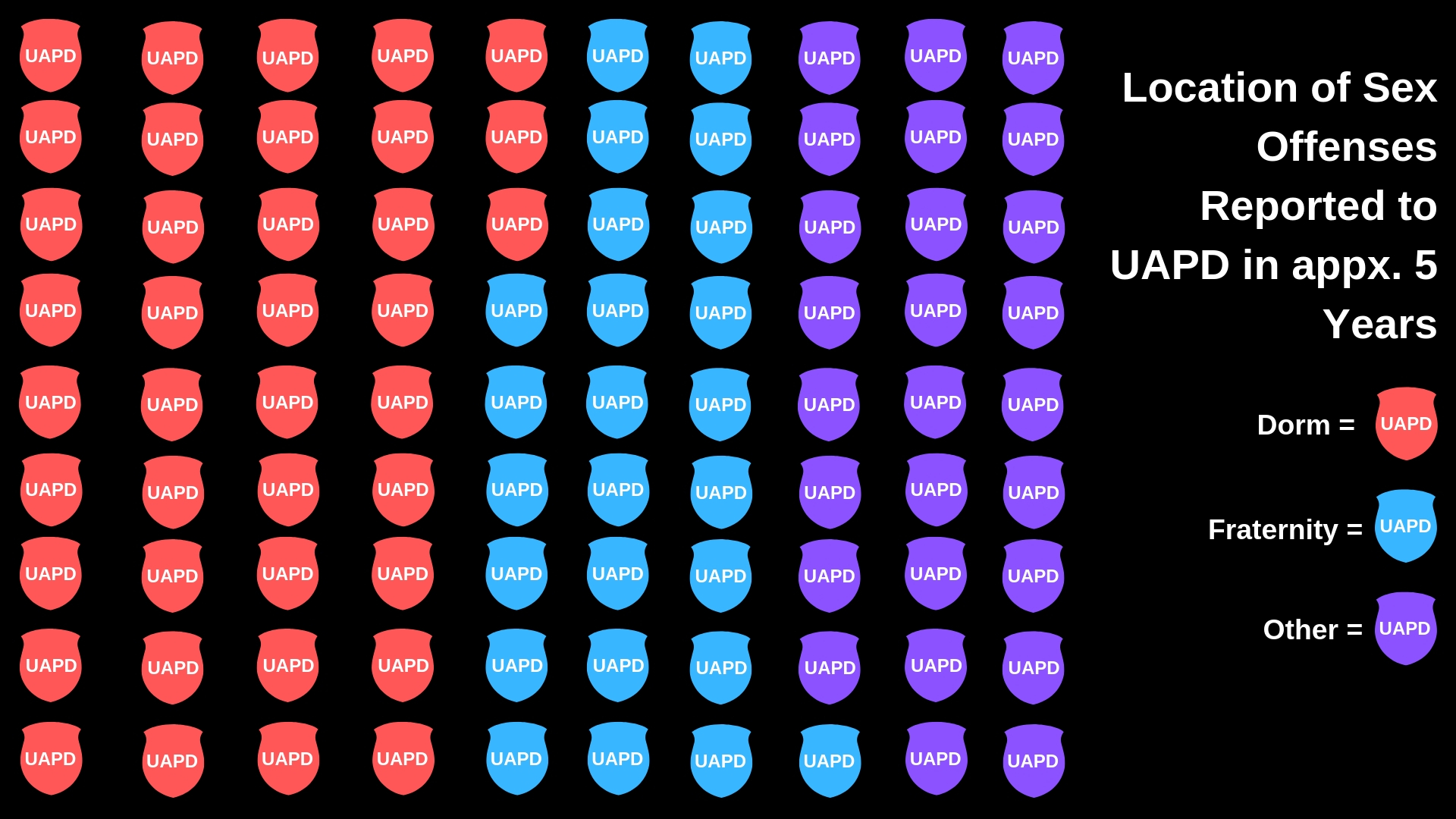

An investigation of sex assault cases at UA found that in an approximately five-year time span, 90 reports of sexual offenses were made to the University of Arizona Police Department. Between Aug. 1, 2013, to Oct. 19, 2018, nearly half of these offenses were believed to have occurred at on-campus student housing and over one-fourth were believed to have occurred at fraternities.

Additionally, there is a noticeable discrepancy between the reality of sexual assault prevalence and the number of official reports made to campus police. UA hired two sexual assault survivor advocates in fall 2018, and within the first five months of their employment alone, 170 students came to see them to discuss a sexual assault.

While the university has started to discuss new methods of education and prevention for campus sexual assault, as well as hire more personnel in different capacities to address these issues, there are other universities in the country making more progress with more efforts.

The case between this student and professor is one of many examples of the UA’s historical fragmentation of policies and procedures for addressing sexual misconduct allegations. At both the institutional and social levels, the UA has failed to rectify sexual violence in sorority and fraternity programs, student housing, and other areas of campus life.

The school completed its internal investigation of Stupiansky in April 2018, determining “it is more probable than not” Stupiansky violated the school’s Nondiscrimination and Anti-harassment policy by “kissing you when he knew or should have known that you were incapable of consenting to such acts.”

University investigations conducted by the Office of Institutional Equity do not seek criminal charges, unlike police investigations.

According to OIE’s letter to the student, OIE recommended “significant action be taken” in the letter, but did not specify further details.

The woman received another letter from OIE on July 2, 2018, confirming Stupiansky was no longer “employed by or affiliated with” the university “in relation to the investigation, determination and recommendation” of her complaint.

Stupiansky’s last day “employed by or affiliated with” the university was June 30, 2018, according to university spokesperson Chris Sigurdson, over two months after the OIE determination was made.

Sigurdson said he could not comment on whether or not his departure was related to the complaint, or if it was due to a voluntary resignation or firing, since personnel records are confidential. OIE would not comment on its recommendation for handling the personnel issue since its investigations are also confidential.

June 30 is the end of the university’s fiscal year, the typical end date for appointed personnel contracts, Sigurdson said in an email.

The Tucson Police Department criminal investigation into the allegations against Stupiansky is still open as of April 2019.

Rick Lougee, Stupiansky’s attorney, disputed the allegations against his client.

“The toxicology results, the text message exchanges and other evidence prove the accuser’s allegations of sexual assault to be false,” he said in an email. “I can only speculate as to her motive to fabricate.”

Lougee also objected to the standard journalism practice of not naming alleged sexual assault victims without their permission.

“If she was actually sexually assaulted, the public will support her if she is named for having the courage to come forward,” Lougee wrote in an email. “If she is lying, as she is, she deserves public shame and obloquy.”

Several reasons contribute to this standard journalism practice; among them is that journalists do not want to create a chilling effect that would discourage more people who believe they were sexually assaulted from filing reports in the future. Those who choose to file sexual assault reports also often fear retaliation that could result in violence or intimidation.

Still, Lougee said in an email that “this policy is based on politics not considerations of journalistic integrity.”

Stupiansky’s past academic research has focused on the study of sexual health and behavior in adolescents. As of March 2019, Stupiansky was listed as a real estate salesperson in Phoenix, according to the Arizona Department of Real Estate license database.

“It kind of destroys your faith in the whole entire school.”

The same day the woman woke up in the stranger’s bed, she said she went to the university’s Campus Health Services to get tested for date-rape drugs. She was tested for Rohypnol and later she asked to also be tested for sedatives such as ketamine and benzodiazepines.

In early October 2017, she received a note from a Campus Health nurse that one of the tests, sent to a lab in Pennsylvania, was cancelled because the “incorrect specimen” was received. The student said there was no further follow-up on the cancelled test.

The student said when asked by Campus Health if she wanted to submit a rape kit, she declined because at the time, she thought rape kits were used only to identify a rapist’s identity. She knew who she had drinks with, so she didn’t think it was necessary. Campus Health never explained to her what its results could show, she said.

“I think it’s important to know that I came in asking for date-rape drug testing and they asked me if I wanted to get a rape kit, but they explained nothing about that process to me,” she said. “They didn’t explain why it would be helpful to get one. I came in disoriented, confused, and I didn’t know the value of getting that at that point in time.”

The student also said that she felt shamed by Campus Health. She said a nurse told her to “make better choices” and “be more careful about who you hang out with.” She said that a school counselor in psych services told her she “didn’t come to school to report a crime” and she might not want to put her energy into pursuing it.

“It was just all the typical stuff that you hear other people say, and I just sort of thought we were past that as a society, but apparently not,” she said.

If a student plans on pressing charges and filing a police report, testing and exams are done at Tucson Medical Center, where a volunteer from the Southern Arizona Center Against Sexual Assault will meet the student, Katherine Schuppert, a doctor in the women’s health clinic at Campus Health said.

If the student doesn’t plan on pressing charges, Schuppert said a provider in the women’s health clinic will meet with the student, but will be advised that any care given in Campus Health does not count as completing a rape kit.

Campus Health can order testing from other labs for date-rape drugs depending on what the patient believes happened or what drugs the patient believes may have been involved, Schuppert said, but without insurance some of those tests are expensive and there is a chance of false positives and false negatives.

“Some labs do certain ones, and some labs don’t, and it all gets pretty complicated,” she said.

The woman decided to submit a rape kit through Tucson Medical Center after visiting Campus Health, which was tested through the Tucson Police Department Crime Laboratory.

Jelena Myers, TPD crime lab superintendent said in an email that the lab has no untested kits. Rape kits are delivered to the lab within days of collection, and they take approximately 38 days to process once they have been delivered to the lab, she said in an email.

“Several initiatives over the last three years have eliminated any previously existing backlogs of untested kits,” Myers said in an email.

The student said the university’s referrals to legal aid were not helpful. The agency the university referred put her in contact with a lawyer who seemed to lack experience in Title IX policy, she said. After submitting an intake form for a different legal aid organization, she was told the organization could not provide assistance because it involved potentially criminal charges.

“They didn’t really take into consideration the fact that I’m a student and I’m not going to be able to afford an expensive lawyer by myself,” she said.

After she received the letter from OIE that Stupiansky probably kissed her without consent, but did not address her allegation of rape, the woman said she felt the school “downplayed” her whole experience.

“It kind of destroys your faith in the whole entire school,” the woman said.

When contacted for an interview about how the internal investigation’s determination was made, OIE employees said questions must be deferred to Sigurdson, vice president of communications and university spokesperson, for comment.

“Privacy laws and university policy and practice prevent staff from releasing any details of OIE investigations,” Sigurdson wrote in an email.

The University denied a public records request for all of the documents under OIE’s internal investigation because “doing so would be contrary to the best interests of the state and to the privacy interests of the complaining individuals and any other witnesses who participate in the investigative process,” the records request response letter said.

Sigurdson said these reports are “private by practice and policy” because they are investigating charges that may be founded or unfounded, and to prevent people from being afraid to report or participate as witnesses in the future.

“Because of the nature of discrimination, harassment, or retaliation complaints, allegations often cannot be substantiated by direct evidence other than the complaining individual’s own statement,” the University’s Nondiscrimination and Anti-Harassment policy states. “Lack of corroborating evidence should not discourage individuals from seeking relief under this policy.”

New campus efforts aim to make UA a model school

The university has started to introduce plans to improve student resources and streamline reporting avenues, but some campus stakeholders say it’s not yet enough.

In fall 2018, UA hired a new Title IX director and two survivor advocates who are not mandated reporters in the Women and Gender Resource Center.

Ron Wilson is bringing years of constitutional and civil rights law experience into his new role as UA’s Title IX director. Wilson has previously served as a Title IX investigator at Edinboro University in Pennsylvania.

Wilson said part of his decision for accepting his new position was because of the potential he sees in student involvement surrounding equity issues. His appointment came at a time when UA was reckoning with its history of 27 sexual and domestic violence investigations into UA athletes and athletic department employees in a six-year span while simultaneously defending itself against Title IX lawsuits, according to reporting from The Arizona Daily Star.

“Students, first and foremost, are a driving force behind this,” he said. “It was clear from the very first moment that Title IX was proposed as an amendment that the intent was to protect students, and so we have to have student involvement, and you have to have student engagement, and you have to have students at the table at every step of the way.”

He said he wants the UA campus to “go above and beyond” what it’s required to do under Title IX guidelines.

In January, Wilson said the university was in the process of hiring more deputy Title IX coordinators to work with him. Also in January, both the offices of Wilson and University President Robert Robbins sent mass emails to the student body about Title IX reminders, ways to connect with the survivor advocacy program, and a campus climate survey regarding sexual misconduct concerns.

The campus climate survey was sent to all UA students on Feb. 1 from the Dean of Students Office and closed on March 3. Westat, a social science research firm, administered the confidential and voluntary survey about experiences with sexual assault and sexual misconduct.

Ron Wilson is the new Title IX director at UA. He previously served as the Title IX coordinator for gender equity in sport and Title IX investigator at Edinboro University in Pennsylvania. Photo courtesy of the University of Arizona.

“The results will be used to guide policies to encourage a healthy, safe and nondiscriminatory environment at University of Arizona,” the email with the survey link said. “It is important to hear from you, even if you believe these issues do not directly affect you.”

The survey is similar to one administered to UA in 2015 but includes slight revisions, Lucas Schalewski, associate director for assessment, research, and grant development, said in an email. The results of the survey should be available in late summer, and the findings should be posted online in fall 2019, he said in an email.

One of the January emails from the president’s office announced the creation of a Department of Title IX, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), which would essentially consolidate the Title IX and Office of Institutional Equity responsibilities. Wilson will oversee the new unit, the email said.

“I remain committed to making the UA a national model for our approach, and the DEI will become a benchmark to which other colleges and universities around the nation will look for guidance, direction, and technical support,” Robbins’ email said.

Robbins was contacted for an interview about the school’s progress of obtaining the changes and assessments outlined in his emails.

“We don’t typically schedule the president for interviews on student projects or research,” Sigurdson responded in an email, “but I can put you in touch with the appropriate administrators over the area of interest. In this case that would be Ron Wilson, copied here.”

Wilson said he is excited about the possibility of deploying campus-wide internal training, prevention, awareness and education programming. He also said UA has the opportunity to become a place where potential Title IX coordinators and investigators can receive training and certification. In the future, he also hopes to see the Consortium on Gender-Based Violence being nationally recognized for its research.

Elise Lopez is the inaugural director of UA’s recently-launched Consortium on Gender-Based Violence. Previously, she was the assistant director of relationship violence programs in the college of public health. In 2015, she served as a U.S. delegate to the Ontario government Women’s Directorate’s Summit on Sexual Violence and Harassment. In 2017, she served as a liaison to a criminal justice task force for the American Bar Association focusing on college student due process rights and victim protections.

“Typically what happens on campuses and other places, whether we’re talking about violence or any other kind of topic, is we spend all these resources and time and energy developing and implementing programs and then we kind of do it as a check box,” she said. “We don’t really evaluate it. Or we do, but we don’t really critically ask ‘did this work or not?’”

One initiative from the consortium is to create an “innovation fund” that would seed fund people’s ideas for large or small projects on sexual assault education and prevention, she said. Students, student groups, faculty and staff would be able to apply for funding for their ideas. The goal is to decide who will get funding to develop their ideas by the end of the spring 2019 semester.

In comparison from five years ago, Lopez said UA is making efforts to try new approaches to education and prevention – a trend she thinks is partially due to increased federal attention on the issue around 2014. Still, UA has never had enough capacity to reach its desired goals, she said.

UA has over 40,000 students, but one person funded as a sexual assault prevention staff member, some graduate assistants and a team of undergraduates tasked with sexual assault prevention programming, she said.

Elise Lopez is the director of the UA Consortium on Gender-Based Violence. Photo by Nividita Chatani/ College of SBS. Picture courtesy of the UA.

“I don’t think there’s anybody who would say that that’s sufficient,” she said. “And yet that’s where the funding level has been. So I think if we really want to make a dent in sexual assault prevention, we have to put more funding toward it. We absolutely need more staff working on this. We need more student involvement. We need more financial resources to help us create more sexual assault prevention programming.”

Over 40% of sexual assaults reported to UAPD happened in student dorms

In April 2016, a student reported to UAPD that she was raped by an acquaintance in the Apache-Santa Cruz dorm. Her report was the fifth sexual assault report made to UAPD in 2016; 21 reports of sexual offenses were made to UAPD by the end of 2016.

The student told police that about a month prior to making the report she assisted a male student back to his dorm room after seeing him “very intoxicated” at Highland Market, according to campus police records. She said she had met the student before through mutual friends, and they had watched TV together. Once the students had reached his room, the woman said he attempted to force her to perform oral sex on him. After she refused, she told police he began sexually assaulting her on his bed.

After she told the student to stop twice, he told her to “stop being lame,” and continued raping her, according to the document of the woman’s interview with UAPD.

She also told police that she had been less social with her friends since the alleged assault and had been staying inside her room for most of the past month since it occurred. She said she decided to file a report that day because she saw the other student again and felt re-triggered.

The residence hall’s community director told police she would offer the woman an emergency relocation to a different dorm. The woman told UAPD she did not wish to press charges against the other student.

Between Aug. 1, 2013, to Oct. 19, 2018, 39 of the 90 sexual offense reports received by UAPD were believed to have occurred in on-campus student housing. In both completed and attempted rapes, about 90% of victims know the perpetrator, according to the National Institute of Justice, otherwise known as acquaintance rape.

In an approximately five-year time span, campus police received 90 reports of sexual violence. Nearly half of the assaults were believed to have occurred in student residence halls, and over 25% were believed to have occurred in fraternity houses. Infographic by Jessica Suriano.

Several apartment complexes for students are located just outside of on-campus boundaries: the Hub at Tucson, Sol y Luna and the Urbane apartments. Between Jan. 1, 2013 to Aug. 27, 2018, Tucson Police Department received four reports of sexual assault at Hub at Tucson and five reports of sexual assault at Sol y Luna. TPD received zero reports from Urbane apartments between its opening date to Aug. 27, 2018.

While almost half of the sexual assault reports UAPD received in a roughly five-year time span were believed to have happened at a dorm, the majority of sexual assaults of students attending large universities occur off-campus, according to data collected by the Associated Press.

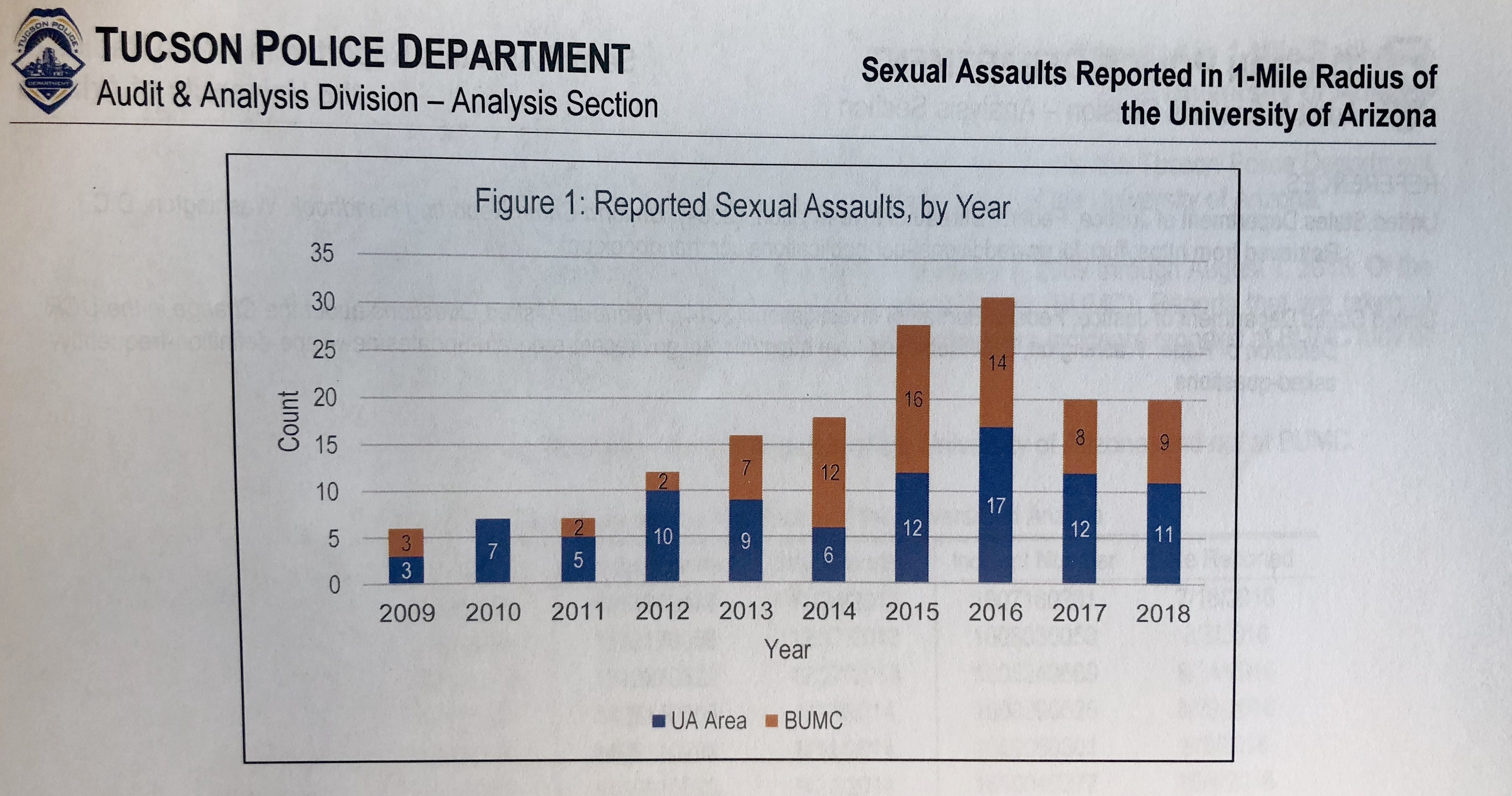

Between Jan. 1, 2009 to Aug. 1, 2018, TPD received 165 reports of sexual assaults within a one-mile radius of the center of UA campus. TPD said information for incidents prior to 2009 was not available, and a change in the FBI’s crime classification system could account for more reports to be counted as a sexual assault after 2013.

“Sexual assault/rape,” as defined by the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Classification System, now allows for more actions taken without consent against a person of any gender to be classified as sexual assault, whereas the FBI definition prior to 2013 stipulated rape as only “of a female forcibly and against her will.”

Of the 165 sexual assaults within a one-mile radius of campus reported to TPD, 73 incidents were reported at the Banner University Medical Center. However, TPD said just because a crime was reported at BUMC does not mean the sexual assault was believed to have occurred at BUMC. Through their database, TPD said they can’t determine how many of the 165 reports came from UA students.

Tucson Police Department received 165 reports of sexual assaults within a one-mile radius of UA campus between Jan. 1, 2009, to Aug. 1, 2018. 73 of these reports were made at Banner University Medical Center. Graphic made by Tucson Police Department and included in records request response.

Annie McCabe was a Resident Assistant in the Arizona-Sonora dorm during the 2015-2016 academic school year while she was an undergraduate student, and she said the resident assistants had to complete a one-week training for handling a variety of situations with students living in the dorms, including sexual assault.

“From what I can remember, the first thing was to state that we’re a confidential source,” she said. “However, if it is something that we feel is of harm to themselves or someone else, we are obligated to report it. So letting them know that we would be reporting it to higher authority if they disclosed something that we felt was of a threat to them.”

While students could disclose to their resident assistants, McCabe said, she said they would stay as involved or as uninvolved as the student preferred throughout the reporting process.

Jamie Matthews, associate director for residential education at UA, said resident assistants are mandated reporters if students tell them that they have been sexually assaulted.

UAPD Sergeant Cindy Spasoff said campus police knows sexual assaults are underreported by the student body, but she also understands it is a student’s choice whether or not to pursue the reporting process through the police.

“I’m frustrated that we live in a society that it’s become socially normalized,” Spasoff said. “That campus sexual assault is just a thing, and I don’t like that. That’s the part that frustrates me. That we haven’t raised our students better, that we haven’t as a society grown into an aspect where this is unacceptable and that we’re not going to tolerate it anymore, and that it continues to happen. That’s the part that’s frustrating.”

UA Greek Life has a sexual violence and harassment problem

Of the 90 sexual violence offenses reported to the University of Arizona Police Department in an approximately five-year time span, over one-fourth were believed to have occurred at a fraternity house on campus.

In that time frame, UAPD received 25 reports of sexual assault or forcible rape that were believed to have occurred at fraternities housing either chapters that have since lost recognition on campus, or remain active chapters as of spring 2019.

Those 25 reports account for about 28% of the 90 total sexual offense reports in this time span. The amount of UA undergraduate students enrolled in a Greek organization is 17.2% – a significantly lower proportion than the frequency of alleged offenses committed at fraternity houses.

At least three studies have found fraternity men are three times more likely to commit rape than other men on campus.

Among the fraternity houses included in the 25 reports are the addresses for Alpha Kappa Lambda, Kappa Sigma, Alpha Sigma Phi, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, Alpha Epsilon Pi, Sigma Chi, Pi Kappa Alpha, Sigma Alpha Mu, Delta Tau Delta, Sigma Phi Epsilon, Zeta Beta Tau, Phi Delta Theta, Theta Chi, Beta Theta Pi, and Phi Gamma Delta.

During the fall 2018 term, Alpha Kappa Lambda lost UA recognition through May 31, 2022 after the Dean of Students office investigated allegations of violating sanctions, possession of drug paraphernalia and threats to harm one chapter member and his girlfriend.

In Summer 2018, Kappa Sigma lost recognition through May 2023 after an investigation concluded chapter members held “events with alcohol while under sanction, assaulted individuals hired to provide security and created a fund to hide activities from the university,” according to a news release from the university. Sigma Alpha Epsilon also lost recognition in Summer 2018 after an investigation into health and safety violations.

Alpha Sigma Phi lost recognition in fall 2017 through May 31, 2021 because of a Dean of Students investigation into allegations of endangerment, unauthorized possession of alcohol and hazing. Delta Tau Delta lost university recognition in July 2015 after the national office suspended the chapter for repeated violations of risk management policies and new members’ poor academic performance.

Alpha Epsilon Pi, Pi Kappa Alpha, Sigma Alpha Mu, Sigma Phi Epsilon, Zeta Beta Tau, Phi Delta Theta, Theta Chi, Beta Theta Pi, and Phi Gamma Delta are still active fraternity chapters within The Interfraternity Council at UA, along with 10 other chapters.

The Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity house at the University of Arizona is known for the lion statues in the front. The SAE chapter at UA lost recognition in Summer 2018. Photo by Jessica Suriano.

“I don’t want to do this.”

In August 2017, a UA freshman who had been on campus for less than a week told UAPD she was raped by a Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity member during a party at the chapter’s house.

David Lipan, 20, is the Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity member accused of pinning this student down by her wrists and assaulting her in a room in the fraternity house while she told him to “please stop,” that she was “too drunk to do this,” and “I don’t want to do this,” according to the UAPD report and Pima County Superior Court records.

The student and her friends were offered shots of alcohol at the party before the alleged assault and were “berated” when they hesitated to drink, and were told “the whole point of frat parties was to get drunk and have sex with a frat boy,” according to interviews included in the police report. The report said the woman also had visible marks and bruising on her neck.

In February 2018, the female student’s former attorney filed a notice of claim for $2.5 million against the university, which stated “The University of Arizona and ABOR [Arizona Board of Regents] knew or should have known of the dangerous propensities of this fraternity, and should have warned students about the dangers there, should have revoked their permission to operate, should have investigated and shut down the illegal parties there, and revoked their authority to operate as a fraternity on campus to protect the students there.”

As a result of the university’s “failure to supervise and investigate this organization on their campus,” the notice of claim states, the woman has “constant anxiety for her safety, nightmares, and fear of trusting anyone or anything.” The woman is also fearful of retaliation from other Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity members, according to the document.

After Lipan was indicted in February 2018, he was permitted by the court to travel to the Coachella music festival in April 2018, to California in November 2018 for the Thanksgiving holiday, to Illinois and California again over winter break, and to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, in January 2019.

On December 5, 2018, Deputy Pima County Attorney Alan Goodwin filed in court a notice that the State of Arizona is intending to prove Lipan has a pattern of past behaviors, outlining a testimony that Lipan allegedly sexually assaulted someone before in Naperville, Illinois, in 2015.

In 2015, Lipan, then 17 years old, picked up a then 14-year-old high school student in his car, and drove her to a parking lot even though the girl thought they were going to a Dunkin’ Donuts, the court document claims.

Lipan then allegedly turned off the girl’s phone, removed her clothes, and began “hugging her in a way she found inappropriate,” according to the document. Then, Lipan forced the girl to perform oral sex on him twice before driving away and leaving her alone in the parking lot, according to the testimony in the document.

Lipan and his legal counsel argued the testimony should not be allowed to be used in the trial for various reasons in court documents, including that there was no police investigation into the alleged assault at the time and that the testimony was taken several years after the alleged assault.

The State disputed these arguments in another court document, arguing that the testimony of the second woman from Illinois demonstrates a pattern of behavior.

In April 2019, Lipan’s defense counsel submitted its list of witnesses and defenses. The document stated Lipan’s team would plan to have another Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity member, the fraternity president, and a UA Title IX investigator testify during the trial, as well as the female student’s parents, brother, and boyfriend.

On January 25, 2019, Lipan rejected his plea deal, which would have entailed Lipan pleading guilty to a class 5 felony count of sexual abuse and 0.5 to 2.75 years in prison, according to The Arizona Daily Star. However, the plea deal also included a possible probation sentence instead of any prison time. Lipan’s five-day jury trial was going to start on March 26, 2019, but was postponed to July 9, 2019, according to court documents. The jury selection is supposed to take place during the last week of June.

Sigma Alpha Mu is currently not under any university sanctions, but during the fall 2016, spring 2017, and fall 2018 terms, the chapter had code of conduct violations for either endangerment or alcohol infractions.

The woman “believes the culture of the University of Arizona must change,” so that assaults will not continue to happen at UA, according to the notice of claim.

When brotherhood becomes dangerous

“There’s something powerful about being a member of a club that has shared symbols and shared secrets,” Alan DeSantis, University of Kentucky professor and author of Inside Greek U: Fraternities, Sororities, and the Pursuit of Pleasure, Power, and Prestige, said in a phone interview. “And that’s part of the attraction, but also it’s part of the danger as well.”

There is a plethora of research available on the sociological phenomena at play in college fraternities, their chapter houses, and parties, but a prevailing idea is that the role of peer support among young men combined with alcohol, newfound freedom from home, and harmful gender stereotypes, can create a perfect storm.

Hyper-masculine men, DeSantis said, can “celebrate guys that are aggressive and violent. They celebrate guys who are ladies’ men, who get laid a lot.”

In his research, he said he found that sorority women were slut-shamed or scolded for exhibiting any type of “overt sexuality” whereas fraternity members were “high-fived” for the same behavior.

Mary Koss, a Regents’ professor at UA in the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, published the first national study sexual assault among college students in 1987.

“Fraternity membership itself does not promote sexual aggression,” she said in an email. “Peer support for competitive sexual conquest, pressure and opportunity to drink to excess, and a physical environment presenting opportunities to rape are risks for rape and are all found in fraternity living.”

Fraternities are not the only places to see similar patterns in male-dominated spaces, according to Lauren Leif, the interim director of UA Fraternity and Sorority Programs. Military groups and sports teams can exemplify this culture too.

“I think those areas, fraternities especially because of the age group, are a place for perpetrators to seek out in a lot of ways,” Leif said. “If you want to find somewhere to hide out, that’d be a good place to do it, right? And have access to people to assault.”

DeSantis also related the ways fraternity men bond is similar to the dynamics at play in military groups, sports teams, or street gangs.

“The more we invest, the more we’re invested in the groups,” he said. “So I don’t think there’s anything really magical about fraternities, per say, but in America, there’s not a whole lot of other groups that specifically do what these organizations do.”

Lauren Leif is the interim director of Fraternity and Sorority Programs at the University of Arizona. Photo courtesy of the University of Arizona.

Marcos Guzman, interim assistant director for UA Fraternity and Sorority Programs, said he tells fraternity men, “I don’t think you create rapists or predators, I think you attract them,” because of the environment that is sometimes created within fraternities. He said the aim of their programming is to address and correct “this kind of sense of toxic masculinity.”

“So that education I think focuses on those students who know that this is wrong and to look for it within their membership because of the environments that are created,” he said. “Like the parties, dark rooms, lights going everywhere, and the music’s so loud, alcohol flowing; how can you possibly know what everyone is doing?”

Leif and Guzman are aware of how fraternities, and their underage members, access alcohol for parties.

“I think we all know it’s easier to get access to alcohol when you’re underage when you have a network of people that are of-age,” Leif said. “And so we know that that obviously contributes to sexual assault across the board.”

Many UA fraternities offer the opportunity for some members to live in the chapter’s on-campus house. Leif said she is “not a fan of fraternity housing.”

She said Greek Row housing at UA originated when there weren’t enough dorms to house more students, but Greek life housing “obviously brings a lot of struggles.” The Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority built the first on-campus house at UA in 1923.

“So it’s kind of funny because we’ve created our own monster,” Leif said.

Parties and alcohol use are common in American universities. At UA, when parties want to serve alcohol, presumably only to people 21 years old or older, they are considered “registered” through the university and typically employ security guards to monitor who is drinking alcohol at the event. Unregistered parties might be included in UAPD reports, and then the chapter would answer to the Greek Standards Board or Dean of Students office, Leif said, and either way, the probable outcome is sanctions.

Leif said her office receives UAPD reports a few times a month about alcohol transports, noise complaints, or other violations, and Guzman said they find out about 90% of unregistered parties. Guzman said sometimes fraternity men might not recognize abuse behaviors from their brothers during parties.

“They think everyone’s a good guy,” Guzman said. “Don’t get me wrong. You have tons of good guys, but you also have to acknowledge you got a lot of bad guys too.”

UA needs to ‘flip the script’ for better sexual violence education

The case against Lipan was able to go through the court system, albeit the time from the report to trial spanned nearly two years, but data shows that sexual assaults at the University of Arizona, including its fraternity houses, are not isolated incidents.

While 90 reports of sexual offenses were made to UAPD in a roughly five-year span, the recently hired survivor advocates in the Women and Gender Resource Center said 170 students have come to talk to them about a sexual assault during the fall 2018 semester alone.

To put this discrepancy into even more perspective, statistically only 20% of female college students ages 18 to 24 report their sexual assaults to law enforcement at all.

UA is making efforts to find new methods of preventing sexual assault, which is necessary considering the programming the university has been using for years has not made any differences, according to Lopez.

“Most of the time if programs aren’t working, people like to ignore it because A: nobody likes to admit failure, and B: it’s hard to find resources to try something new,” she said.

Some colleges have adopted programs such as Green Dot and other bystander intervention trainings, but Lopez said “even the best bystander education programs do not have evidence that they change actual behavior or rates of violence on campus.”

The Green Dot program aims to train students, faculty and staff to “interrupt situations that are imminently or potentially high-risk for violence,” according to the Alteristic website. Dorothy Edwards, Ph.D., is the president of Alteristic, a civic and social organization company, and the creator of the Green Dot program.

However, there is one program called EAAA – Enhanced Assess, Acknowledge, Act – that was written about in the New England Journal of Medicine and was shown to prevent rape up to two years after people completed the program.

“It’s literally the only program that’s ever been shown to actually prevent rape, and it was done in Canadian universities,” Lopez said. “The uptake on it in the U.S. has been really slow because it takes money and capacity to do it. And a lot of universities have not been willing to invest in that, unfortunately.”

The EAAA program was designed for first-year women university students. It was created to teach women risk cues for sexual violence in others’ behavior, defensive strategies in the event of feeling threatened, and to stop blaming themselves or others who have been sexually assaulted.

Still, many in higher education advocate for better ways of teaching people not to rape rather than teaching people how to protect themselves from getting raped.

Jackson Katz, a social researcher, asked men what they do on a daily basis to avoid being sexually assaulted. Then he asked women. pic.twitter.com/GjniLR4iIZ

— Jennifer Wright (@JenAshleyWright) September 30, 2018

Lopez is trained in EAAA, and so is Thea Cola, the Women and Gender Resource Center’s coordinator for sexual assault and violence prevention, Lopez said. Lopez wants to roll out that program to the campus in fall 2019 and implement in for a five-year span, so they applied for funding from a private foundation and are waiting to see if the money will be granted.

“And so really, we’ve known for more than 30 years at this point, that about one in four women will experience attempted or completed rape on college campuses in the United States, and that rate has been the same ever since then,” she said. “We’ve hardly seen the needle move.”

Although Lopez said the UA community is talking more about sexual assault than in past years, there are still programs at play, many aimed toward fraternity and sorority members, that are not effective because they are not targeted enough.

“In the past five years, one of the things we’ve seen all the way from the federal government level to our social discourse level, is this idea that we shouldn’t just be focusing on how to not get raped on college campuses,” she said. “We really need to be talking about perpetration prevention, and although anybody can perpetrate sexual aggression or violence, most sexual aggression and violence is perpetrated by men, and so a lot of the discussion has been around: how do we engage men in violence prevention programming?”

Guzman and Leif said the main programming for Greek-affiliated students is a four-tier system called Advocating Sexual Assault Prevention created through the Women and Gender Resource Center. For the first two tiers, 60% of every fraternity or sorority is required to attend the programs. Tier three, a six-week program called Wildcat Way, requires at least one student from each chapter. Tier four, a two-credit course, has not launched yet, but at least one student from each chapter is supposed to enroll in it once available. New members of a Greek organization also take online programming about drug and alcohol abuse.

At orientation, new students see a presentation from campus police and the Dean of Students office about health and safety concerns. The PowerPoint presentation obtained from the Dean of Students office includes one slide with sexual assault facts.

Often, messaging is also not coming from people who look like all students and are representative of different communities, Lopez said.

“So one of the complaints that many colleges and institutions hear about their prevention programs is that they’re too white,” she said, “they’re too heteronormative and they’re too cisgendered.”

Historically, sexual assault education programming for men has proven to be challenging, according to Lopez, because most men do not see themselves as perpetrators or potential perpetrators, so they disengage entirely.

“Most men are not interested in sexual violence prevention and don’t see it relevant to them, so they’re not going to show up to workshops called – that have titles or descriptions around – toxic masculinity or healthy masculinity,” she said. “They’re not thinking about their masculinity, you know, in the way that most women are thinking about their own gender roles.”

Tyler Rodriquez, a junior at UA and peer educator in Students Promoting Empowerment and Consent – SPEAC – said what differentiates toxic masculinity from its healthier form is the expression or suppression of specific emotions to fit a societal standard of what behavior is ‘acceptable’ in men.

“You automatically know it’s toxic when it’s affecting yourself and others adversely,” he said. “So if you have anger management issues or if you are troubling people emotionally just with how you’re acting or how you’re presenting yourself, that’s a clear cut sign of basic toxic masculinity.”

Aysia Arias, a senior UA student, is also a peer educator for SPEAC in the Women and Gender Resource Center. She said masculinity becomes unhealthy when “gender roles are followed with violence.”

“I feel like from a very early age, boys are socialized to either not cry or not show emotions or be competitive,” she said.

Toxic masculinity contributes to men dying by suicide about 3.5 times more often than women, she said, showing that it harms not only others in society but also men themselves.

The Me Too movement has furthered the conversation of toxic masculinity in the media landscape, too. Arias said it wasn’t until joining SPEAC that she started understanding what toxic masculinity meant, and Rodriquez said Me Too helped shift the topic into the public view.

“I think we really need to flip the script on how we approach it,” Lopez said. “And I think it’s also going to take more than quick fixes.”

Debating the pros and cons of university Greek Life

Guzman and Leif said there are positives to joining the 17% of UA undergraduate students enrolled in a Greek organization, such as higher retention rates of Greek students versus non-Greek students, larger professional and social networks, and increased chances of finding a successful job after college.

“You can look at it at the bottom dollar; Greek students are typically more engaged with the university and its system, and are more likely to give back once they’ve graduated,” Guzman said. “Employers seek fraternity and sorority members at a much higher rate due to their leadership experience.”

Both Guzman and Leif also said Greek-affiliated students have higher retention rates between freshman and sophomore year. At UA, they are almost 10% more likely to continue on to their sophomore years than students who are not a member of a Greek organization.

“In addition to that, more likely to receive a job offer that they wanted to receive,” Leif said. “You can probably find a job, not necessarily the job that you want, and Greek students are finding the job that they want.”

The construction of the Geraldo Rivera Greek Heritage Park was made possible by a $500,000 donation from TV journalist Geraldo Rivera and his wife, Erica. It is located between North Cherry Avenue and North Vine Avenue on Greek Row. Photo by Jessica Suriano.

DeSantis, author of Inside Greek U, said in a phone interview that the opportunities Greek-affiliated students see after college might not have “a whole lot to do with the effect of the Greek organization.”

In his book, DeSantis cites numbers from the Center for the Study of College Fraternity: 85% of U.S. Supreme Court justices have been fraternity men since 1910 and 85% of Fortune 500 executives have been fraternity men.

“While it’s impossible to say because we’re not running two simultaneous universes, I would hazard to guess that those that become leaders, would have become significant leaders in the business world or the legal world or the political world with or without the impact that the Greek organizations play,” DeSantis said.

Sorority and fraternity memberships can come with hefty price tags that are not conducive to many students’ budgets. At the University of Arizona, the Panhellenic sorority chapter with the priciest new member fee is Gamma Phi Beta at $2,552, according to the spring 2019 costs of membership. Active member fees including housing costs for Panhellenic sorority chapters can total between $3,000 to just over $4,000. The Interfraternity Council chapter at UA with the priciest new member fee is Sigma Chi at $2,600. Active member fees including housing costs for Interfraternity Council chapters can total between about $2,000 and up to $6,000.

In a 2015-2016 survey of 1,260 undergraduate UA students, of those students who indicated they were members of a social fraternity or sorority, 49.7% were white whereas only 4% identified as Asian/Pacific Islander, 10.5% as Hispanic or Latino, 15.8% as multiracial, and 16.7% as black or African American.

“Unfortunately I think the role that they serve is antithetical to the goals of higher education,” DeSantis said. “That they’re surrounded by like-minded people, almost always from the same social-economic and ethnic groups, and in fact, I think it retards the sense of intellectual and cultural growth that we hope happens at higher education, universities and colleges.”

With more than nine million alumni of fraternities and sororities in the job force, Greek alumni networks are reinforced with every new graduating pledge class. Alumni networks equal support for a university, both in loyalty and money.

At least one study concluded that male alumni of Greek organizations donated significantly more money to their alma maters than non-Greek students. DeSantis’ research shows these alumni members are the same ones occupying powerful leadership roles in many professional spheres.

DeSantis, who was a fraternity man in college, said “humans are inherently gregarious,” and there are “very few people that are solely individualistic and isolated.” Even students who don’t pledge to a chapter will seek out a close-knit group of friends, he said.

“So I think what Greek organizations do, is they give us a club to belong to, and they give us these shared narratives that we buy into, kind of like a religion,” he said. “And it elevates these clubs. These clubs are more than just a bowling club. These are your ‘brothers’ or ‘sisters,’ and we live in a house together, and we suffered through pledging together.”

The UA also has chapters for historically black fraternities and sororities, known as the Divine Nine. DeSantis said his research showed black Greek organizations create “lifelong ties” more effectively than predominantly white Greek chapters.

The majority of the Divine Nine chapters are members of the United Sorority and Fraternity Council, which also includes identity-based chapters not included within IFC or Panhellenic. Some examples are Delta Lambda Phi, a fraternity founded by gay university men, or Gamma Rho Lambda, for queer, transgender, non-binary and allied students.

DeSantis said he found that “elite groups,” Greek chapters that have the highest or most sought-after social standing and large networks, have “far less diversity” than lower-tier chapters, or ones with less social capital.

“On my campus, I can almost – give me two guesses, and I can tell you what fraternity or sorority my students are in, just by the way they look,” he said.

Is it time to shut down the party?

Over the past couple of years, some universities have decided to indefinitely suspend their entire Greek life systems.

Not only would this remove over 100 years of history and tradition from campus, but it also wouldn’t help mitigate sexual assault or binge drinking, according to Guzman. At least with an established structure for fraternity and sorority programs, there is a protocol system with some oversight, he said.

“If we have our programming and our office and that reach to those students, isn’t that a little bit better than just kind of flushing them out there, where we have no idea where they are or what they’re doing?” he said.

Despite improvements that need to happen, Leif said there is still a valuable place for Greek organizations on UA’s campus.

“I think the Greek experience is a valuable one,” she said. “Obviously there’s a lot of areas that need to be kind of fixed up. And when universities make a decision to close all our chapters – or remove recognition is really what they’re doing – what they’re doing is creating a culture where they’re punishing all of the good organizations on behalf of the bad organizations.”

Fraternity and sorority chapters engage in a significant amount of philanthropy and fundraising, which some say is overlooked when new headlines about Greek life make the news cycle again. According to the most recent information on the IFC website, in the 2013-2014 academic year, IFC members raised over $20 million for philanthropy. According to the 2017-2018 National Panhellenic Council report, collegiate Panhellenic members raised nearly $28 million for philanthropy.

Although DeSantis said he had a positive and important experience as a fraternity member in college, in hindsight he has been able to critically reflect on the Greek university system. He said if fraternities and sororities continue to attract students, they should probably not be directly affiliated with universities.

“Without significant reform, and we can just look at the state of Greek life today – not only the number of deaths from hazing, but the number of sexual assaults on female visitors, property damage – it needs serious reform or it should be abolished,” he said.

The Context: Students face barriers during and after reporting sexual assault. Advocates say a culture shift is needed to change the big picture.

Why sexual assaults are underreported

Brenda Lee Anderson Wadley and Karyn Roberts-Hamilton, two confidential survivor advocates, started their new jobs at UA in August 2018. In the first five months of the survivor advocates working on campus, 170 students came to see them to discuss a sexual assault.

The knowledge that sexual assaults are underreported is not new. Statistically only 20% of female college students ages 18 to 24 report their sexual assaults to law enforcement, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network – RAINN. When rapes are reported, 80% of them come from white women even though black women, multiracial women, and Native American or Alaskan Native women in the U.S. are more likely to be assaulted than white women.

One U.S. Department of Justice study found that about 6% of cisgender men reported experiencing attempted or completed sexual assault since entering college.

College students who identify as transgender, genderqueer, or gender non-conforming are more likely to be sexually assaulted compared to students who identify as cisgender, according to RAINN.

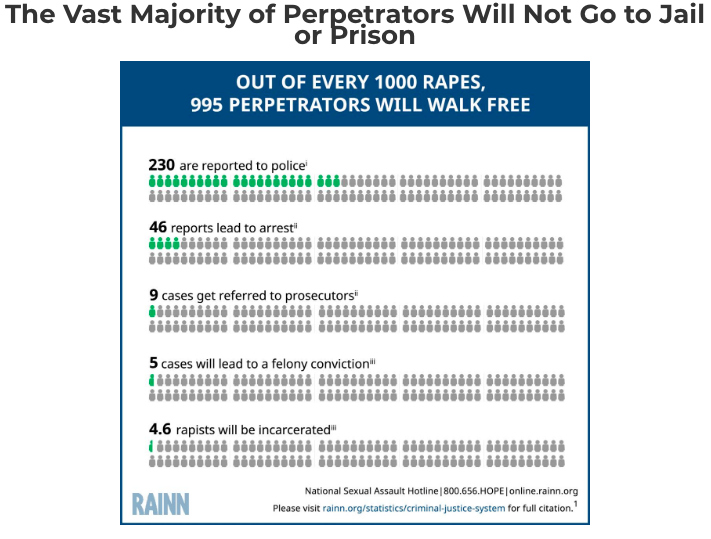

Only 230 out of every 1,000 rapes perpetrated in the U.S. are reported to police, and of those, 46 reports lead to an arrest, nine cases are referred to prosecutors, and five lead to a felony conviction, according to RAINN. Accused rapists are less likely to serve a sentence in jail or prison than perpetrators of robberies or assault and battery crimes.

Infographic by the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

“The U of A is a microcosm of the U.S., and so I think a lot of times people are like ‘Oh, we’re at U of A, we’re in this bubble, nothing bad happens,’ however statistics state that 1 in 4 women on this campus have been impacted,” Anderson Wadley said. “And then when you look at the community with folks who may have a disability as well as our trans students on campus, those numbers are even higher.”

So, why isn’t sexual assault reported more often? Survivors, advocates, researchers and law enforcement officials cite many reasons, including fear of retaliation and believing the police would not or could not help.

Many research studies place the rate of false sexual assault reports in the range of 2% to 8%. Still, UA survivor advocate Roberts-Hamilton said many students are scared of not being believed, receiving victim-blaming comments, or not feeling supported by people they trust if they file a report. She said many students have no interest in pursuing a Title IX investigation, and in fact, the Title IX process can seem “intimidating or scary” to a lot of people on campus.

“And so sometimes, once we explain the Title IX process, students decide that they do want to do that,” Roberts-Hamilton said. “But my thing is always like, with Title IX, you might not get the outcome or the consequences that you want. So, if we move forward with this, what are you going to get out of just the process? Is it going to be a part of your healing? And that’s not something that we can determine for students, they have to make that choice for themselves. But it is common that students are re-traumatized in the process.”

UA students who chose to report a sexual assault have faced victim blaming in the past. In February 2015, a student reported that she was raped in the Apache-Santa Cruz dorm to UAPD. After the student made the report, she received a Facebook message from the mother of the student accused of the rape, according to UAPD records.

“You may want to drop the charges filed, as you are only going to hurt yourself,” the Facebook message said. “As a polygraph test will prove his innocence and word is you ‘get around.’ I have names of girls on your floor to confirm this to be true.”

The mother’s message continued to say she planned to sue the student who filed the report for defamation because the student was “messing with another person’s future.”

“If you are a decent human being with a heart, you will stop this from moving forward,” the mother wrote in the same Facebook message. “He has never been in trouble. You both were at fault[;]you both are guilty. You will suffer the consequences for lying.”

Victim blaming exists in other spheres, too, such as the judicial court system. A New Jersey Superior Court judge is facing a three-month suspension after asking an alleged sexual assault victim “if she tried closing her legs to prevent the attack,” as recently reported by The Washington Post.

Amidst Brett Kavanaugh and Christine Blasey Ford’s 2018 testimonies regarding her allegations of being sexually assaulted by the now-confirmed Supreme Court Justice, President Donald Trump tweeted his doubts of Blasey Ford by writing, “…if the attack on Dr. Ford was as bad as she says, charges would have been immediately filed…”

I have no doubt that, if the attack on Dr. Ford was as bad as she says, charges would have been immediately filed with local Law Enforcement Authorities by either her or her loving parents. I ask that she bring those filings forward so that we can learn date, time, and place!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 21, 2018

In true Twitter form, the platform exploded with survivor stories marked by the hash tag “#WhyIDidntReport.” The outpour of stories solidified countless reasons why survivors often choose to keep their trauma to themselves for years, and sometimes forever, and also why sometimes they remember their traumas but don’t remember the minutiae of the experiences.

Because my boyfriend told me he would actually kill me if I left him or if I told anyone and when someone beats you, you believe them. I didn't want to die. #WhyIDidntReport

— Lizz "Executive Time" Winstead (@lizzwinstead) September 21, 2018

I was humiliated. I knew everyone would find out. I was afraid it would ruin my professional reputation before I had even started. I was afraid they would not believe me and let him hold my grade back. I was afraid they would not let me graduate from law school. #WhyIDidntReport

— Amee Vanderpool (@girlsreallyrule) September 21, 2018

You know #WhyIDidntReport? Because when I finally did, I lost my athletic scholarship and had to drop out of school.

— daisy! (@taisydackett) September 21, 2018

The fear of disclosing a sexual assault is present in Campus Health too, according to Almader. She said students worry about their parents seeing a bill from Campus Health, even if the reason for the visit is confidential. Sometimes the cost of a visit to Oasis is a financial burden as well, she said.

Oasis offers one free first visit, and any counseling visits after that cost $25 each. Almader said there is a donation-based funded for students who are completely unable to afford therapy, but it is very small.

The Pima County Attorney’s Office offers victim compensation to pay for expenses such as medical consultations, mental health services or loss of wages from work. There are limitations to this funding. The victim of the alleged crime must be willing to cooperate with law enforcement officers and prosecutors, and assistance is not guaranteed just by applying for the funding. Pima County’s Victim Services Division can assist with referrals for counseling or providing advocates to accompany a victim throughout the court process.

Police and community dynamics can hinder reporting

Look at the people around you and tell them about the best sex you’ve ever had. Uncomfortable? Now consider how it would feel to tell them about the worst — a sexual assault.

That was what UAPD Sergeant Spasoff said she was told during part of her police training for sexual assault reporting. She said everyone might have different reasons for choosing not to tell the police about being sexually assaulted, including the fear that police officers will victim-blame during investigations, which discourages them to report crimes. However, she said she thinks UAPD has made progress in ceasing harmful practices.

“There is a little bit that people feel like police are victim-blaming, and while I understand and respect that, I don’t like that,” Spasoff said. “It’s a very difficult process long-term where the person is re-victimized over and over again at no fault of their own, just by the process of the investigation, the court appearances, having to face the aggressor. So being able to already be vulnerable, that takes a lot. And for somebody who’s trying to overcome, and survive, and move on, that may not be the best option for them.”

Anderson Wadley said the “historical and community trauma around marginalized identities” and relationships with law enforcement can also play a role in a chilling effect for reporting sexual assaults on campus. Also, many students might also not want to disclose a sexual assault perpetrated by a male student if the police officer interviewing them is a man, she said.

“So few students that I’ve seen – like so few – are interested at all in contacting the police or have,” Roberts-Hamilton said. “And I spend so little time talking about that as an option. I think that there is, I get the sense that there’s just – not stigma because I think it’s based in truth – that the police aren’t great at handling cases of sexual assault, and that there is the very real possibility or probability that students will be re-traumatized. Or, that nothing will happen. That is, with all of the stuff that’s come out about untested rape kits, I think that’s also a barrier just to going to get a forensic medical exam. It’s like, ‘OK, and then what? My kit is going to sit in a storage locker for 20 years? Where am I going to be in 20 years?’ There’s a lot – there’s a lot of layers.”

Spasoff said the main issue UAPD sees on campus regarding sexual assault is a lack of established consent between partners, which often involves drug and alcohol use. The university needs to establish more bystander intervention programming, she said, and not just in the context of sexual assault prevention, but intervention for many types of crimes common on campus.

“Like somebody stealing a bicycle – we can’t even get people to stop and take a minute to report when somebody’s taking a bicycle from another person,” she said. “Because to them, it’s not that big of a deal. But to the student that’s having the bicycle taken, it can be life changing.”

UAPD and the Dean of Students office give presentations at new student orientations for both students and their parents. Spasoff said the UAPD presentation to parents is important because a lot of the new students are entering college without ever having a conversation about consent.

“We really like to stand up and kind of get on our soapbox and say like, ‘we don’t want your child to come to this school and the first conversation they have about sex is with one of us,’” Spasoff said.

Survivor advocates want to see a culture shift

The two new survivor advocates who started working in the Women and Gender Resource Center said an institution of UA’s size should have between six to eight advocates.

“I would love to see our campus do a much more significant investment in prevention work,” Roberts-Hamilton said. “Most of the prevention that is done at the U of A is done by undergrad students, who are very minimally paid. We could be doing a lot more there.”

President Robbins has been “incredibly supportive” of the new advocacy positions, and promised to find more money to hire more advocates, according to Roberts-Hamilton. Still, she said it will take more than money to see a change in campus culture.

“I think that we could do a lot with the resources we already have, it’s just about collaborative work,” she said.

Both of the advocates entered their new positions with extensive backgrounds in trauma-informed care.

Decorated T-shirts were on display around The House of Neighborly Service, 243 W. 33rd St., for Take Back the Night Tucson 2018 on April 11, 2018. Take Back the Night is an annual event for communities to raise awareness about sexual violence and support survivors. Photo by Jessica Suriano.

Anderson Wadley was working in UA Student Assistance, supporting students through suicidal ideations and mental health hospitalization. She said she came in contact with sexual abuse survivors in her previous position too as a mandated reporter, but she always wanted to eventually provide students with confidential support.

Roberts-Hamilton worked in non-profits for five years before studying violence as a public health issue in graduate school. Before the advocate position was created, she worked in the Women and Gender Resource Center on sexual violence prevention.

Anderson Wadley said the culture shift needed at UA can’t be only student-led, and there has to be support for it coming from the administration too.

“So how and in what ways has the administration backed survivors or backed helping people who have had terrible experiences here because of the impact of gender-based and sexual violence?” she said.

Minnie Almader is the coordinator for Oasis, the branch of UA Campus Health for sexual assault and trauma treatment, but she’s also the only licensed professional counselor designated to Oasis counseling. She said when her schedule gets full, which it often does, two other staff members trained in trauma will help see students. She said additional resources, whether it be more counselors or assistance with outreach services, would be “really helpful.”

“I think all over the U.S., college students have a lot of stress, they have a lot of fear about their future, and I think the Me Too movement has really made more people aware of sexual assault and harassment and stalking,” she said.

Almader said she wants more men involved in the discussions about sexual assault prevention and educational outreach “because when the loved one is hurt, it affects everybody,” she said. “It affects your relationship; it affects your family; it affects your friends.”

The Solutions: Universities around the country have started to implement new programs, but potential Title IX reform could change everything.

Proposed Title IX changes add another layer of challenges

The concerns about the future of sexual assault prevention and Title IX policy are not exclusive to the University of Arizona and can be seen nationwide.

In September 2018, Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony about the now-confirmed Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh reignited both passionate support and vehement disbelief of survivor stories, including on the UA campus.

On Oct. 9, 2018, the Counselors for Social Justice Club held an event called “Empower Hour: Supporting Sexual Assault Survivors” to write letters to Blasey Ford and politicians about their support, disappointment or calls to action.

Frannie Neal, president of the club and graduate student, said they wanted to use the event to advocate for sexual assault survivors and criticize the decision to appoint Kavanaugh to the highest court in the country.

“Unfortunately I think that this is more of a setback than a move forward,” Neal said. “I think that women, now, might not feel like if they even come forward, that they will be believed, or that it matters. So, I think that it has a huge ripple effect.”

University of Arizona students write letters to Christine Blasey Ford and U.S. senators during “Empower Hour” on Oct. 9, 2018. Students were encouraged to express their thoughts about the outcome of the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings in the letters. Photo by Jessica Suriano.

U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’ proposed Title IX policy changes, which have been a significant point of controversy since they were introduced to the public.

The proposed changes to Title IX regulation would grant greater protections to students accused of sexual misconduct and decrease liability for universities, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education.

The Obama administration set guidelines on handling sexual misconduct investigations for colleges that receive federal funding in 2011, but DeVos rescinded them in 2017.

The national debate about these proposed changes quickly erupted, dividing survivor advocacy groups and people who argue that universities did not protect students’ due process rights under the previous Title IX guidelines.

Some UA stakeholders are concerned these proposed changes would make an already fragmented reporting and sanctioning process more convoluted.

Roberts-Hamilton, one of the survivor advocates at UA, said Title IX investigations “take way too long,” and students who are found in violation of the university code of conduct for sexual assault are not facing consequences as serious as the actions they perpetrated.

One of the most contentious provisions outlined in the proposed changes is the right of an accused student to have the accuser cross-examined. The cross-examination would be conducted by a lawyer or other adviser, and upon request, the parties could be in separate rooms while the cross-examination is completed with the use of technology.

Anybody who is accused of sexual misconduct is entitled to due process rights, Elise Lopez, director of the UA Gender-Based Violence Consortium, said. However, setting up systems that have already proven to re-traumatize victims could lead to less people wanting to report, “especially if they feel like they’re going to be treated like they are lying or like they’re complicit in their own sexual assault or that they’re going to be aggressively questioned in a live cross examination,” she said.

“It’s essentially setting up a quasi criminal justice system on college campuses,” Lopez said.

Ron Wilson, UA’s new Title IX director, said in an email he plans to ensure a safe educational environment for all students “if or when” new Title IX policy is implemented by the courts or Department of Education.

“I want to focus on what we know we have to do, and what we know we can do, and what we know we should do, regardless of what Washington D.C. thinks,” Wilson said in an interview. “And I’m confident that with the level of student involvement and concern and interest that we’re seeing here now, we’re going to get there.”

Colleges could also opt to use a higher standard of proof under the proposed changes. Instead of using “preponderance of the evidence” standard, which means it is more likely than not that misconduct occurred, colleges could use the “clear and convincing” standard, which is a more difficult threshold to prove with evidence.

“I would disagree with using a higher standard of proof,” Lopez said. “Somebody being suspended or expelled from campus for a conduct code violation I think has lesser implications than somebody getting a criminal record and going to jail or prison.”

Colleges would also only be held accountable under Title IX for investigating sexual misconduct complaints that occurred on-campus or during a school-sponsored activity.

This is problematic and “will definitely be harmful to people” because the majority of sexual assaults at large universities happen off-campus, Lopez said. The proposed changes do not clarify if Title IX would cover sexual assaults that happened to students while studying abroad, which is a university-sanctioned activity outside the U.S., either, Lopez said.

“So it complicates and muddies what’s going to actually count,” she said. “And it doesn’t mean that institutions can’t do anything about sexual assault that happens off campus or outside of the U.S., but what it means is that if they – if an institution does a bad job of handling those – they’re not in violation of the student’s civil rights under Title IX.”

If a student were to report a sexual assault that happened outside of campus boundaries or outside of university-sponsored activities, the university would not have to investigate it under Title IX, but they should, Lopez said.

The university wouldn’t be expected to conduct “a civil rights-quality of investigation,” according to Lopez.

“And you know, we like to think that institutions would do the right thing, but historically we haven’t always seen that happen,” she said.

The student who accused former UA professor Nathan Stupiansky of rape said she does not support DeVos’ proposed changes for a few reasons. She said investigating reports of off-campus assault, especially in the contexts such as her report involving a faculty member, is “still so relevant to protecting UA community.”

“How could they not have an ethical obligation to look at that, or a legal obligation to look at that?” she said. “That’s crazy to me.”

The proposed changes, if passed, would be codified into law, not only as guidelines like the Obama-era recommendations, so the UA Title IX office would have to adhere to them. Wilson said he doesn’t want the potential changes coming from the Department of Education to be the driving force behind how the school handles misconduct reports.

“Regardless of what they say out of Washington D.C., you’re a student, and I don’t care whether you’re here on main campus or if you’re in Paris, if something happens to you, I want to know about it and I want to make sure that you get all the help that is available,” Wilson said.

Colleges could also opt to employ an “informal resolution process, such as mediation, that does not involve a full investigation and adjudication,” at any time if both parties voluntarily agree to it, according to the proposed changes.

Informal processes could mean mediation between students, restorative justice or other methods of resolution.

Anderson Wadley said resolution and healing processes for survivors are not “one-size-fits-all,” so universities should be exploring alternative methods of what justice looks like to different students.

Roberts-Hamilton said she has met with students who want mediation, and sometimes “justice to them doesn’t look punitive,” but we don’t have a model for that on campus. Mediation is not the best solution for all survivors, she said, but having the option “would more holistically support many survivors on campus.”

“There are models like that,” Roberts-Hamilton said. “There are lots of ways that conversations can be facilitated in healthy ways that support survivors and prep perpetrators to be accountable. It is not a long-shot; that is not a wild dream.”

Lopez said she thinks “mediation is wholly inappropriate for sexual assault” because it is premised on the idea that there is a compromise to be made and dispute to resolve.

“Sexual assault is not a dispute,” she said. “You have a person who was clearly harmed and a person who clearly committed that harm and you don’t want to come to a compromise. You want to come to an agreement about how that responsible person might readdress or repair that harm.”

However, Lopez said there is a difference between mediation and restorative justice, and the ladder has the potential to “safely and effectively” handle some cases of sexual assault if there are mechanisms in place to hold the parties accountable.

“And it can only be used with people who are willing to take responsibility for the harm they committed,” she said. “Restorative justice is different than mediation. Restorative justice is premised on the idea that when somebody commits a harm, they’re responsible for repairing it to the extent possible, and it’s voluntary, so it’s not adversarial where we’re concerned with fact finding and determination of guilt. And so I think that Title IX needs to be more clear about the language it’s using.”

To adopt informal resolution policies, Lopez said schools need to ensure they are not forced on all students looking to file a report, and facilitated by somebody who’s trained in restorative justice and in the dynamics of sexual assault and intimate violence.

“It can’t be just, we facilitate a dialogue between these two people and then somebody gets off the hook for what they did,” she said.

DeVos and supporters of the proposed changes claim the measures will strengthen due process and consistency at universities after the Obama-era guidelines weakened the presumption of innocence until proven guilty for accused students.

“As educational institutions, we have a responsibility to provide equity to all students, whether they’re a complainant or a respondent,” Lopez said. “So what that means for us is how can we create an experience for respondents that respects their constitutional rights, that respects their educational rights, that is an educational process? And that if they’re found responsible, how do we put it within our educational mission to give them sanctions that are educational and therapeutic and will keep them from harming somebody else in the future?”

SAVE Services, a Maryland non-profit that says it works “for policy reform to protect all victims, support due process, and stop false allegations,” released an open letter of support for the proposed changes signed by nearly 300 professors or lawyers. Two UA employees signed this letter as well as one Tucson lawyer.

Daniel Asia, a UA professor of music, and Dave Seng, a UA lecturer in the school of information, and Tucson attorney Steven Sherick signed the open letter that states, “false allegations of sexual assault dissipate scarce resources and undermine the credibility of victims.”

Many peer-reviewed research studies place the rate of false sexual assault reports in the range of 2% to 8%. SAVE Services’ website propagates that up to 90% of rape reports made to police can be false, but that statistic originated in a study that has since been deemed untrustworthy because the majority of its sources were not credible and “based on unscrutinized police classifications,” according to an analysis of sexual assault research studies.

Sherick is the defense lawyer representing UA student and Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity member, David Lipan, against a 2017 rape allegation made by another UA student.

The window for the public to submit comments to the Department of Education about the proposed changes closed on Feb. 15.

Other universities try to find more effective prevention and resolution methods

Other universities in the U.S. have started to test new ways of handling sexual assault reports, improve student resources and increase risk mitigation in Greek life organizations.